How To Ask Job Interview Questions: A Do’s And Don’ts Guide

By now, we as employers all know how to prepare for job interviews. We know how to read resumes in advance, analyze the candidates on paper, and prepare interview questions. Then, with the interviewee sat down across from you and with the interview scoresheet in hand, you open your mouth to speak, and then … nothing. Your mind goes blank and you stutter to ask the interview questions you put in so much effort to prepare.

Sounds like you or something similar? Don’t worry. It’s happened to me, and even experienced interviewers. The do’s and don’ts in this article will guide you on the basics of what to actually say and how to say it in order to ask the interview questions that you need to ask.

Most importantly, if you only take away one thing from this article:

The easiest and recommended way to ask job interview questions is to simply read the questions as they are written on the interview question sheet or scorecard. This will ensure consistency across all job interviewees as they will all be hearing the same exact question.

Is that really all? All will be clarified below, so read on.

Read The Questions As They Appear On The Question Sheet

As mentioned above, if you are a total beginner at being an interviewer and just need to get through it, the easiest thing you can do is to read aloud the interview question as it is written on your question sheet or interview scorecard.

In fact, this is recommended even for experienced interviewers as well for a variety of reasons. In fact, I would consider this best practice.

The reasons and benefits for doing this are:

- Maintains consistency between different interviewees in how the question is asked and how the question is perceived.

- Consistency here translates to less biased answers from the interviewee and less biased judgments from the interviewer.

- Maintains consistency between different interviewers asking the same question.

- This reduces the chances of asking the wrong question or leaving the question up to different interpretations of different interviewers.

- Reduces cognitive load on you, the interviewer, to think of what to say.

- I.e. You can focus your brain power on listening and judging the answers, rather than thinking of how to word your questions.

- Reduces any anxiety the interviewers might have in ‘getting things right’ at the interview.

- I have seen many interviewers get stressed about interviews, and the easiest way to not mess up is to just read the questions aloud.

This is the simplest but effective solution to the question of “what to say at an interview”. Unless you are a master interviewer, there really isn’t any other method that beats this.

I will admit that doing it this way does sound robotic, repetitive, and even unnatural. However, a structured interview is supposed to be, well, structured, with things following a process.

Also, each candidate will only meet you once and hear each question once. Reading things out will only sound repetitive and unnatural to you, not them. Furthermore, the focus of the interview is on their answers; the questions are just the starting point.

All that said, if you are going to read the questions off, then you have to make sure that the questions are written appropriately and fit for purpose. No point in reading a tongue twister of a question that is not even relevant. If you are looking for interview questions you can use, check out our Interview Questions Bank.

Don’t Ask Biased Questions Or Make Leading Statements

Related to the previous point, whether or not you are going to read off the questions, make sure you do not bias or ‘lead’ the interviewee to answer the question in a particular way. The interview is a test after all and we want to make sure we are testing on even ground.

To explain this, let me use a few examples.

An example of a straightforward and neutral question would be: “What is more important, compliance or creativity, and why?”

In transforming that same question into a leading/loaded one, we would get: “What aspects of creative work do you like the most?”

Adding a leading statement to the original question, we could have: “Compliance is very important in our company. Do you prefer compliance or creativity at work, and why?”

In the second and third examples, the question itself or the statement attached to it can lead the interviewee to answer the question in a certain way. Any interviewee, upon detecting that ‘positive comments about creativity’ (or vice versa) are what the interviewer wants to hear, will answer accordingly. They will do probably so even if they hold the opposite opinion, and you will lose the chance to learn what they truly think.

Furthermore, if all the interviewees answer in the same way with the same bias, then you won’t be able to compare them. E.g. if all the interviewees say that compliance is very important to them (whether they truly believe it or not), then you won’t be able to differentiate amongst them on this factor.

In contrast, the first example keeps things fairly neutral, and the interviewee’s answer and opinion could swing either way. It makes it more likely that the interviewee will answer based on what they think, rather than what they think you want to hear.

I understand that for some jobs, it is a bit of a giveaway what the ideal answer is (i.e. obvious compliance-related or creativity-related jobs), but for most jobs, it could go either way. This is why you want to hear what the interviewee naturally thinks.

Be careful with this one. Sometimes, in making the interview a little more conversational or in an attempt to ease the interviewee, I’ve seen managers inadvertently say things that could bias the interviewee’s answer. Even things like “you know we’ve got one of the most creative teams in the company” or “if you join us, you’ll be working with one of the most compliant teams here; we won the award for that last year” in an attempt to sell the job could bias the interviewee’s answer.

I know I sound like the ‘pedantic police’ by telling you you can’t even put a ‘comment or two’, but again, the purpose of the interview is to hear what the interviewee has to say. In a sense, you already had your say in the job advert.

Therefore, as a baseline, make sure that your questions are worded in as neutral a way as possible. In addition, when asking the question, make sure you don’t add to the question or ask it in a way that could lead the interviewee to answer in a biased manner.

(Do) Ask The Question And Remain Silent: Let The Interviewee Answer Unbiased

Linked in with not asking lead questions or making leading statements, I have seen interviewers take it to the extreme and make too many statements. So much so that the interviewer has spoken more than the interviewee.

I have seen interviewers ask a question, and in an attempt to simplify the question, kept explaining the question until they had practically answered the question for the interviewee.

I have also seen situations where, just after the interviewee has barely answered the question, the interviewer jumps back in to ramble on about the question or the job and does not let the interviewee speak.

Again, the purpose of the interview is to hear what the interviewee has to say and learn about them. Making unnecessary comments or statements will just distract from that at best, or further bias the interviewee’s responses at worst.

Stay objective: Just ask the question and let the candidate answer in peace while you silently judge their answer.

But what if the interviewee’s answer is not sufficient? What if they really do not understand the original question or did not answer the question well enough? Surely you would have to say something then?

Yes, which leads me to the next point.

(Do) Have Follow-Up Questions At The Ready

In reality, interviews are no always smooth affairs where you ask a question, which is perfectly understood by the interviewee, and they respond in kind with an answer that perfectly fits the S.T.A.R. interview answer model. At the same time, anything unplanned that you say could potentially bias the interviewee. What is an interviewer to do?

The best you can do is to come prepared. And you can do that by having follow-up questions prepared and preplanned. These questions should be thought through and consistent, and pre-’approved’ as questions that will not bias the interviewee. There are a few ways this can be achieved.

The first type of follow-up questions are the ones that prod the interviewee to fully answer the question. These types of questions are useful if the interviewee did not fully answer the question, did not use the S.T.A.R answer model to the fullest, or if you want to clarify their answer.

Examples of these standardized follow-up questions are:

- Just backing up a bit from your answer, what was the background situation or context?

- After understanding the situation, what did you implement or put into action?

- Based on your answer, what challenges did you face along the way and how did you overcome them?

- So, what happened in the end?

- Based on what you said, what went well and what didn’t go so well?

- You mentioned a lot of team effort, but what was your part in the team?

- This idea that was implemented, exactly whose idea was it?

For ease of reference and consistency, have these follow-up questions listed just below the main question. Alternatively, have these questions listed as frequently asked follow-up questions or go-to follow-up questions that you can quickly ask.

For more examples of these types of follow-up questions, have a look at any question on our Interview Questions Bank, then scroll down to have a look at their related Follow-Up Questions.

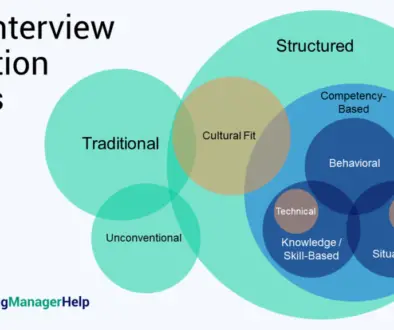

The second type of follow-up questions are ones that change the main question type from one to another. I like to call them “question type converters”. The following example can better explain how they work:

You ask a knowledge-based question, such as “what is the process for X?”, and the interviewee answers in a way that makes you want to test them more. From here, you can turn the original question into a behavioral question by saying “tell us about a time when you successfully worked through the process for X in the workplace?”.

Conceptually, it may be difficult to see why would interviewers want to use these types of follow-up questions. However in practice, an interviewee’s answer may seem too far-fetched, or you may want to test the interviewee more. In these cases, asking essentially the same question again but in a different format will test the interviewee by making them answer the question again in a different way. If they can answer it well a second time, you can be sure the interviewee knows what they are talking about.

Examples of these “question type converter” follow-up questions are:

- Conversion to a knowledge question:

- Can you run through the steps you took to do that?

- Can you tell me the principles that guided you while you took that action?

- Conversion to a behavioral question:

- Can you give an example of when you had to do that in the past?

- Has this scenario ever happened to you before? And if so, can you talk about it?

- Conversion to a situational question:

- Say the conditions changed. Instead of X, Y happened instead. How would you handle the situation in this case?

- (If the interviewee cannot come up with a real-life example from their past) Imagine that this scenario actually happened to you. How would you deal with it?

Don’t Give Feedback During The Interview

After you have asked the interview question, the interviewee has answered, and you have cleared any follow-up questions, you aren’t out of the woods yet. At this point, you might be tempted to react to the interviewee’s answer or even go so far as to give feedback on their answers. I’m here to tell you that you don’t need to or should you do that as it might bias the interviewee’s subsequent answers.

For example, I have seen an interviewer say “that’s the wrong answer” in response to an interviewee’s answer about a process. After that, when asked about anything process related, the interviewee would only say that they would “understand what the process is at the organization and follow said process” and left it at that. Basically, the interviewee ‘hid in their shell’ so to speak and did not fully engage in the interview after that point. Any attempts to really assess the interviewee and their answers after that point were also impossible.

On the other hand, the same could happen for positive feedback to answers, such as “yes, correct”, or “ that’s exactly the answer I was looking for”. While it might feel very natural to give positive feedback (which is what you would do in a regular conversation), it might embolden the interviewee to more outrageous things they might not normally say, such as over-promise on their abilities.

You have to keep in mind that an interview is not a regular conversation, it is a psychological test. You want to keep things as neutral as possible and get the most realistic answers from the candidate.

So what do you do if you can’t give feedback, then what can you do? Simply move on to asking the next question. Assuming that the interviewee has answered the question completely enough, and all follow-up questions have been asked, there is no need to linger on the question.

I will admit that it will feel unnatural at first. If it feels too unnatural, you can react with a nod, or an ‘OK’, but don’t go beyond that. A small reaction should be enough. The idea is that this part of the test is done and it is time to move on.

Keep this up until you reach the end of the interview. If you are unsure what to do at the end of the interview, see our guide here.

Conclusion

If you have been reading this article closely you will have noticed a pattern here. How to ask interview questions is all about increasing consistency and reducing bias in the interview questions and answers. This comes from the ‘why’ of interviews: the interview is a psychological test to accurately differentiate the candidates and determine the best person for the job. Whatever you do, and however you are doing it, as long as it is moving towards these goals, you will be fine.

Happy Interviewing!

Sources

No sources this time. This article was written based on my training and experience on the job.